Personality and Corporate Culture

The role of personality and corporate culture in driving good conduct and compliance

Summary

Failures of corporate culture are rarely out of the news. From PPI mis-selling to LIBOR fixing to the latest allegations surrounding HSBC, unethical behaviour is hugely destructive for the organisations and individuals concerned, both reputationally and financially.

At MDV Consulting, we firmly believe that companies can address the people aspects of effective conduct and compliance. In this article, we outline:

- how better recruitment practices can help you to avoid rogue employees and recruit people with a predisposition for good conduct and strong compliance; and

- how you can create a corporate culture that is conducive to ethics and that prioritises long-term success over short-term gain.

The first is more straightforward and requires HR professionals to use appropriate recruitment and assessment solutions. Like many technical challenges, we can identify the issues and resolve them by making changes in only a few places, which will lie within the boundaries of our organisations. While we might not always get it right, it is within the realm of our knowledge and experience.

The question of culture is more problematic. It requires us to work systemically across functional teams. We must ensure that the whole system reinforces the right behaviours and that line managers, who originate business risk, can spot and manage the wrong ones. This requires us to look at wider socioeconomic and political factors: people’s values, beliefs, roles, relationships and attitudes to work. These issues are difficult to identify, easy to deny and require change in many places, often outside the organisation. This is an adaptive challenge, where we still seek many of the answers.

Identifying desirable characteristics in potential employees

To implement a technical solution to better recruitment, the first step is to consider the characteristics you want – and those you don’t – in the people you employ. It’s simple to identify behaviours that are conducive to good conduct and effective compliance, which cluster around what we would call ‘conscientiousness’. Behaviours that can undermine compliance are similarly easy to spot, and are seen in mavericks and non-conformists.

But we also want more than just conscientiousness from our people. We want entrepreneurs, who are commercially astute, have an eye for an opportunity and are great at winning work. We want excellent interpersonal skills, with the ability to collaborate and handle client relationships. And we want a long list of personal qualities, from the ability to motivate others to resilience in tough times. Faced with a seemingly endless set of attributes, how should you proceed?

The trick is to be discerning. Through job analysis techniques, you can focus on the truly differentiating behaviours that contribute to superior job performance. This allows you to identify a manageable number of attributes, which you can then assess through a multitude of tools and methods, depending on how rigorous you want to be in mitigating the risks you perceive.

When strengths become risks

However, the paradox is that behaviours that help us in one work situation can be damaging in others. Our personal strengths, if overplayed, become the very things that trip us up. If we’re not careful, then our conscientiousness morphs into risk aversion. Instead of following the rules, they bind us. Confidence can harden into arrogance and an entrepreneur can turn into a maverick. And pragmatic adaptability, if taken too far, becomes inauthenticity, with others not knowing what we stand for or hope to achieve.

The model we use in our assessment and development work looks at both sides of this. It helps people to understand their strengths and how to get them in play, and makes them aware of the risks of overplaying them. We also examine areas where people can develop, by making a conscious effort to address behaviours that are neither innate strengths nor risks.

Additionally in cultures with long hours, sleep deprivation can affect the ability to make the right decisions to manage risk, deal with serious issues effectively and exacerbate potentially derailing factors.

Additionally in cultures with long hours, sleep deprivation can affect the ability to make the right decisions to manage risk, deal with serious issues effectively and exacerbate potentially derailing factors.

We can therefore add self-awareness to the list of attributes to look for, along with the need to exercise judgement as things become more nuanced. People can improve their self-awareness and learn to manage their behaviour through proper feedback, training, coaching and role-modelling. This is straightforward in concept but line managers need to be sufficiently skilled, enabled and rewarded to support this effectively.

Objectively assessing your candidates

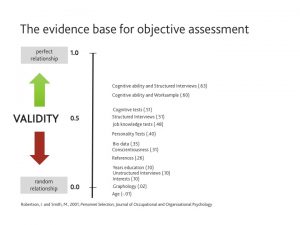

We have some 40 years of data on which tools best assess certain characteristics and predict people’s performance in the job. Despite this, organisations still rely too much on poorly designed recruitment methods. Successful people often think they can spot talent as soon as it walks through the door, not realising that their unstructured interview or ‘fireside chat’ is prone to all sorts of bias and error. As a result, they select candidates who look and sound like themselves. In reality, an unstructured interview is little better than plucking names from a hat.

We have some 40 years of data on which tools best assess certain characteristics and predict people’s performance in the job. Despite this, organisations still rely too much on poorly designed recruitment methods. Successful people often think they can spot talent as soon as it walks through the door, not realising that their unstructured interview or ‘fireside chat’ is prone to all sorts of bias and error. As a result, they select candidates who look and sound like themselves. In reality, an unstructured interview is little better than plucking names from a hat.

As a minimum, we advocate a structured assessment approach, in which you focus on defined criteria. This means examining the ‘what’ – the essential knowledge and experience for the role – as well as exploring the ‘how’ – the key behaviours you want to see. Many tools and approaches exist to help you and using multiple methods will increase your chances of making a good hire. Your challenge is to select the most reliable and valid tools or techniques from a crowded marketplace.

Looking at behaviour beyond the individual

So far, we have looked at straightforward approaches that require organisations to leverage the know-how that’s out there. The difficulty is that this only considers behaviours at the individual level. There are many flaws in this but we will consider two key ones:

- People are susceptible to changing their behaviour, so it conforms to the norm in their organisation.

- Relying on rules to keep individual behaviour in check invariably encourages narrow thinking and legalistic interpretations, instead of moral decision making.

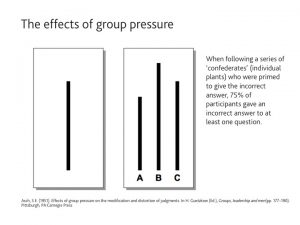

The effects of group pressure

The effects of group pressure

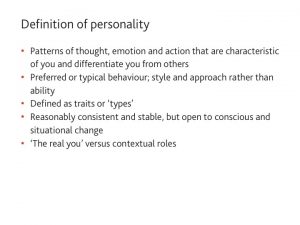

A generally held definition of personality would suggest that people’s traits are stable over time. However, it is well established that people adapt to their surroundings. In the workplace, we are shaped by what is encouraged and rewarded by what is discouraged. We’ve heard the recent debate speculating whether the setting of challenging goals and the linkage of these to large financial incentives, encouraged risky behaviour in the financial sector. Our definition of personality therefore recognises people’s susceptibility to these environmental influences.

A fundamental idea in social psychology is that people want to do more than make money – they also want to feel good about themselves. As it’s hard to feel good when knowingly doing something that could be ruinous to others, where do bad workplace behaviours come from? It may be someone satisfying a sociopathic craving for power, status or acceptance, which leads them to disregard their impact on others. Examining the direction of an individual’s motive profile would help to understand this more fully.

However, even people predisposed to conscientious and ethical working can behave malignly. A culmination of factors essentially corrupt them, ranging from a lack of structure, support and leadership to cultural barriers. Cognitive dissonance explains how, by manipulating beliefs, you can delude yourself into thinking that your objective is worthwhile.

However, even people predisposed to conscientious and ethical working can behave malignly. A culmination of factors essentially corrupt them, ranging from a lack of structure, support and leadership to cultural barriers. Cognitive dissonance explains how, by manipulating beliefs, you can delude yourself into thinking that your objective is worthwhile.

The Asch conformity experiments are a striking example of people publicly endorsing the group response, despite knowing it was incorrect. This is a depersonalization process, whereby people expect to hold the same opinions as others in their ingroup and will often adopt those opinions.

The accounts of the way in which LIBOR was set and the unabashed conversations between traders are an example of this in action, but conformity doesn’t require financial incentive or malice. The Three Mile Island accident showed how a group of people can all be misled into holding similarly incorrect views. The severity of the accident directly resulted from the operators’ failure to break a cycle of assumptions that conflicted with their instrument readings. The problem was only diagnosed when a fresh shift of operators arrived, bringing a different mind-set to the situation. By this time, major damage had been done.

The dangers of relying on rules

The second potential flaw with existing approaches is that we rely on rule-based processes to keep individuals in check.

Of course the basics are important and are often overlooked. Your organisation should have a formal code of conduct that every employee has to recertify each year; mandatory compliance training; appropriate rules for customer-facing employees; a preapproval process for gifts; and swift investigation of problems, with fair and decisive consequences for transgressors.

However, organisations tend to measure the inputs and confuse dissemination of knowledge with compliance. This approach can only have limited success. Enron, after all, had a 64-page manual that outlined its mission, core values and ethical policies. The oil and gas and construction industries also demonstrate the flaws of a rules-based approach. After many years of trying to get to grips with health and safety, they only made the breakthrough when they realised the solution lay in their employees’ attitudes and behaviours. Once they looked at the whole ecosystem, rather than its individual parts, their efforts gained real traction.

This means that even the best-constructed codes, rules and monitoring regimes are of limited worth, unless your organisation’s values are embedded and modelled in your whole working culture. De-risking a culture is difficult. Your senior management cannot be everywhere, so your culture is only satisfactorily embedded if it functions dependably when no one is looking.

An ethical approach to leadership

So how do you create a compliance culture? The answer is that it comes from your people and particularly your leaders.

So how do you create a compliance culture? The answer is that it comes from your people and particularly your leaders.

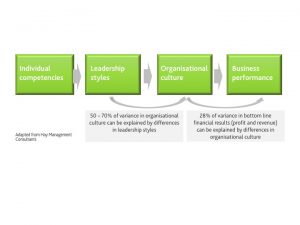

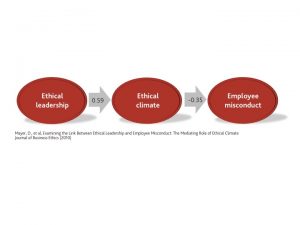

Research by Hay Management Consultants showed that different leadership styles explained 50-70% of the variance in organisational culture. Mayer et al also identified a significant positive correlation between ethical leadership behaviours and an organisation’s ethical climate, and a significant negative correlation with incidences of employee misconduct.

We therefore need an ethical approach to leadership, which goes beyond the ethics of obedience. This means knowing what you need to do andhaving the courage to act on it. However, the question of how to define and measure ethical leadership has not been resolved and there is substantial confusion about what concept even means.

We therefore need an ethical approach to leadership, which goes beyond the ethics of obedience. This means knowing what you need to do andhaving the courage to act on it. However, the question of how to define and measure ethical leadership has not been resolved and there is substantial confusion about what concept even means.

In our view, the behaviours most relevant to ethical leadership include:

- honesty and integrity, including actions that are consistent with your organisation’s espoused values;

- behaviour intended to communicate or enforce ethical standards;

- fairness in decisions and distribution of rewards, with no favouritism or use of rewards to motivate improper behaviour; and

- behaviour that shows kindness, compassion and concern for the needs and feelings of others.

- critical thinking and being evaluative, taking a more considered approach to the impact of decisions.

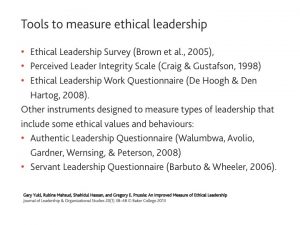

You can measure these traits, using techniques ranging vary from psychometric assessments to specially designed tools that purport to assess ethical behaviour more generally. Some use self-reporting, while others draw on employee or subordinate inputs.

However, it is more difficult to establish a link between these traits and the performance of a leader’s work unit. As yet, no study has examined the extent to which ethical leadership can enhance work unit performance independently of the leader’s other behaviours. Unethical behaviours may even lead to increased short-term performance.

However, it is more difficult to establish a link between these traits and the performance of a leader’s work unit. As yet, no study has examined the extent to which ethical leadership can enhance work unit performance independently of the leader’s other behaviours. Unethical behaviours may even lead to increased short-term performance.

We do, however have plenty of data that shows good leadership and sound human-capital management practices more generally lead to superior business performance. Ethical leadership is thus a key element in every leader’s job specification, both at recruitment and in your assessment of their continuing suitability.

Balancing short-term pressures and long-term goals

Achieving long-term goals in the face of short-term pressures is perhaps the defining leadership task of our times. We know that the long-term matters most but feel the short-term crowding in on us. This means leadership has never been more difficult or more important. Succumbing to unethical practice is a leadership choice, so companies must build their own internal competence and develop a robust culture to withstand the inevitable pressures.

There are real consequences for those who uphold ethical behaviour, especially in the short term. Business may be lost or budgets missed. Local managers can face demands from their seniors at headquarters, who are willing to turn a blind eye but will feign ignorance and dismay when bad behaviour is revealed. Middle managers and frontline employees are often made the scapegoats and whistle-blowers have been hounded and mistreated.

This means that to have a truly ethical culture, everyone must be a leader, not just the man or woman at the top. In our work with groups of leaders, we often see that people can have a powerful impact without a position of authority. We ask participants to identify good and bad leadership examples from a pack of cards. On these cards are the faces of hundreds of leaders from around the world, past and present, and from all walks of life. The one person invariably selected is Rosa Parks, the civil rights activist. People followed her because of the way she behaved, not because she had a powerful position.

More generally, citizens and consumers are increasingly demanding that organisations do the right thing for the long term. They judge major companies such as Facebook, Google and Apple not just on the quality of their products and services but on how they intend to use their influence and the incredible volumes of data they have gathered on so many of us. Taking a long-term view will ultimately be the best way for organisations to succeed. To rise to the adaptive challenges we face, we therefore need to engage everyone and not look solely to those in authority.

Conclusion

We can identify the characteristics required for ethical conduct and compliant job performance. We can deploy tools and approaches that we know predict success and cast off the techniques of the past.

To make this holistic and meaningful, we must look at both the person and the working culture we create. What matters most, however, is that we all display leadership. To have an ethical organisation with strong compliance, we must demonstrate purpose, courage, character, integrity and honesty, as we constantly push to meet our long-term goals.

A personal adaptive challenge

A life of integrity requires us to remain conscious of our decisions. Considering the following questions can help you to navigate the challenges and stay focused on the long term.

1. Start with the end in mind

Defining your personal purpose gives your business purpose a solid foundation. What will be your north star? In 20 or 30 years’ time, what will you look back on? Even five years from now, what do you want your colleagues to say and think when they review the decisions you took today?

2. Consider a world of world of multiple stakeholders

How will your decisions affect colleagues, customers, communities and others? Will your decisions benefit them? How will they feel? Or is your decision solely about maximising shareholder returns?

3. Imagine that your decisions become public

How would you feel if your decisions were trending on social media and the lead story on the evening news? Could you justify your choices, knowing they were ‘right’?

4. Balance law with logic and care

It’s easy to comply with the law and apply reasoning and commercial logic, but are you doing the ‘right’ thing? Are you going beyond the ethics of obedience and your legal obligations?

5. Create an open climate

The shadow you create as a leader will be powerful for those around you. How can you create a micro-climate in which dissent is allowed, prevailing norms are challenged and people feel able to speak out? How will you inspire and model the ‘right’ behaviours?

For more information please contact: Mike Vessey